The Geography of

California

Why visit California?

California is one of the most beautiful and diverse states in America. With its dramatic coastlines, fertile valleys and rugged mountain ranges. It is a state of striking contrasts, with many natural wonders. The Sierra Nevada contains the highest mountain in the United States (excluding Alaska), and the Yosemite and Sequoia national parks. In the southeastern corner are the vast areas of the Colorado Desert, the hottest and driest region of the country; and in the opposite or northwestern corner are the damp coastal redwood forests. Each of these places has unique beauty.

Contents

Map

Relief map of California

Relief map of California

What is the landscape of California like?

The appeal of California is in its variety—in terrain, climate, and wildlife. Mountain ranges extend from northwest to southeast, and between them are the fertile plains of the Central Valley. Outside all this are the great barren, desert lands of the south, and the hills and mountains of the far north.

Coast

The Pacific coast is irregular, with numerous capes and bays. Along the coast runs the mass of the Coast Range, around 65 miles in width, made up of innumerable ridges and spurs, and small valleys drained by short rapid streams. This range averages from 2,000 to 4,000 feet (600–1,200 m) in height, and is divided in its length by long narrow valleys and crossed by numerous tectonic fault lines.

South Coast

The South Coast from San Diego to Los Angeles is a vast summer resort. The soft, luxurious climate, the picturesque scenery, and a score of attractive beaches with familiar names like Malibu, draw countless thousands of people from all parts of the world. The coast is low and sandy, with fertile plains in a setting of palms and orange trees, vines and flowers.

The coast however is separated from the interior deserts by various mountain ranges from 5,000 to 7,000 feet (1,500 m–2,100) high, and with peaks up to the snow-capped Mount San Antonio at 11,000 feet (3,350 m). Here rise the high mountains of the San Gabriel range, the Sierra Madre, and the San Bernardino, while the plain is broken in many other directions by hills and mountains of lesser height. To the north of the city of Santa Barbara, the Sierra Santa Ynez mountains crosses the coast, coming down to the sea in gigantic promontories.

Opposite Santa Barbara, the Channel Islands stretch against the western horizon. These islands are a veritable garden of the sea, with trees and flowers nourished by sunlight and freshened by sea mists. Every headland is a point of interest with enormous arch rocks and sea caves. Sealions are numerous, and there are large pelican rookeries as well as a multitude of other birds. Dolphins and porpoises play in the waters, and sometimes whales can be seen. In the shallow waters there are amber forests of kelp swaying in the ever-changing currents, giant starfish, sea-urchin, jellyfish, sea anemone, and the yellow, silver, and blue of countless fish.

Central Coast

The Central Coast is a mixture of sandy bays and rocky cliffs, with a cool, even temperature and abundant moisture. This is a lovely coastland of valleys, hills, and mountains. From the park-like reaches of the lower slopes the scenery changes to the wilder grandeur of the rugged highlands until you reach the northward sweep of the crescent of Monterey Bay. Here is a matchless panorama, a land of living color, the azure blue of the seas and skies, the vivid green of Monterey cypress and Monterey pine, and the silver white of surf along its glittering beaches.

San Francisco Bay enters through a rift in the coast called the Golden Gate. It is the most largest and best protected harbor on the west coast of North America, nearly 50 miles long and about 9 miles wide.

Golden Gate Bridge

Golden Gate Bridge

North Coast

The North Coast is broken into rolling hills sometimes cultivated to their very tops, othertimes crowned with dark forests. Here the tall redwoods rise from the valleys and crowd the slopes of the encompassing hills. Held within a lofty basin is Clear Lake, a large fresh water lake twenty-five miles long and surrounded by mountains, fertile valleylands, and dark woodland.

North of Clear Lake lies a wilderness region, the interlocking spurs of the Klamath mountains. This is one of the most rugged regions in California, it combines valleys and canyons, bay shore and forest. This is the kingdom of the California redwoods—the tallest trees on Earth. Sequoia sempervirens grow in their native state only in the Coast Range, and nowhere else in the world. They attain their perfection in the scenic region stretching northward from the Golden Gate to the Oregon border. Dense forests of redwoods cover both mountain ridges and river plains with millions of stately trees, majestic in size.

Shasta Cascade

Northeast California is the Shasta Cascade country, a high volcanic plain averaging 5,000 feet (1,500 m) above sea level. It is dry and barren, lying between precipitous mountain ranges. On the east, the Warner Range, containing many high peaks runs straight northward along the Nevada boundary.

On the west, the towering white form of Mount Shasta dominates the landscape. This is an ancient volcano with a double crater, steam still emerges from the higher crevices, and molten sulphur bubbles out near the summit. From the summit of Shasta (14,179 ft / 4,322 m above sea-level) one of the most magnificent views to be enjoyed anywhere is revealed. Shasta rises two miles above the general level of the country which it dominates, and it is twice as high as any mountain within fifty miles.

Central Valley

The interior of California is the Central Valley, a vast basin between the Coast Range and the Sierra Nevada foothills. It extends north and south about 450 miles with an average breadth of 50 to 60 miles. It is closed at the north and south, and thus the Central Valley is surrounded by mountains, with just a single entrance, the gap behind the Golden Gate near San Francisco.

Sacramento Valley

The Central Valley on the north consists of the Sacramento Valley, the basin of the Sacramento River. This is one of the most fertile regions of the world, the valley, with its surrounding foothill lands, embraces ten million acres adapted to agriculture.

The Sacramento River begins as the Pitt River which flows out of Goose Lake in the northeast corner of California, which forces its way around the bulk of mighty Shasta, and down the canyon of the upper Sacramento, which is there a torrential river. To the east the ascent to the Sierra Nevada up either the American River Canyon or the Feather River Canyon is most striking, especially in midwinter, when the transition from flowering gardens to snow-clad ridges is dramatic in its suddenness.

Feather River Canyon

Feather River Canyon

San Joaquin Valley

The south part of Central Valley consists of the San Joaquin Valley. This valley rivals the Sacramento in its great extent and its fertility, but is not so abundantly watered. The San Joaquin River gathers its waters from the Sierra Nevada mountains in the heights above Fresno.

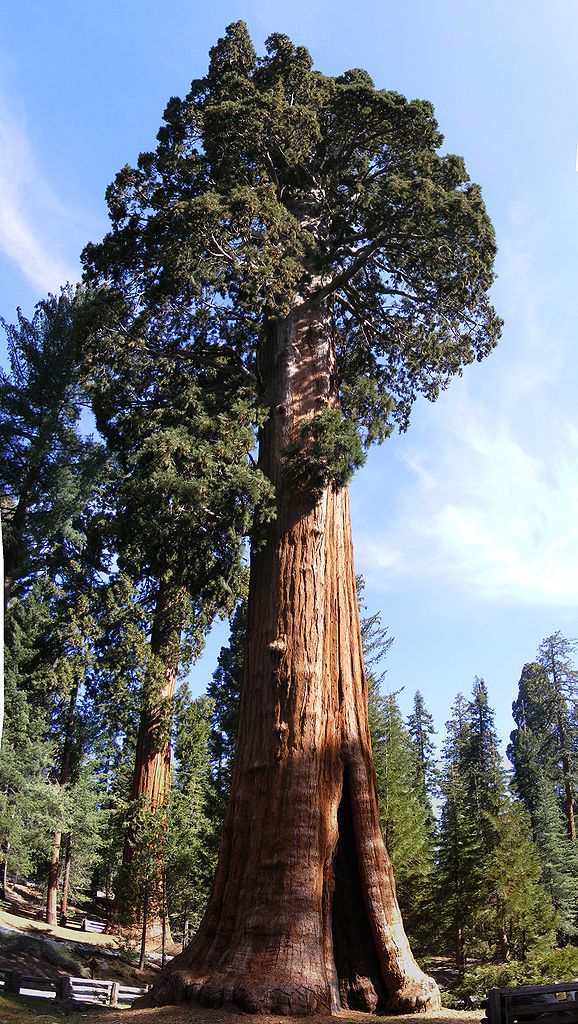

On the western slopes of the Sierra Nevada within easy reach of the San Joaquin Valley is the Sequoia National Park, home to the giant redwood (Sequoiadendron giganteum)—not the tallest, but the most massive trees on Earth. These trees occur naturally only in groves on these western slopes, and here stand thousands of them, many of them more than ten feet in diameter and thousand of years old. Most visitors straightway make a pilgrimage to the General Sherman Tree, the largest tree in the world.

South of Fresno the San Joaquin Valley becomes a somewhat circular, dry, and fairly level plain, about 100 miles long by 80 miles broad. The west part of the plain is a low basin called Tulare Lake. This was once a 25-mile expanse of freshwater lake, but its waters having long since disappeared for agricultural irrigation. To the south are the Tehachapi mountains usually regarded as the dividing line between northern and southern California. The mountain pass is made up through the town of Tehachapi which reposes in a rich summit valley, almost 4,000 feet (1,200 m) above sea-level, the mountains rising as high again.

Sierra Nevada

In the east part of California is the magnificent Sierra Nevada, the finest mountain system of the United States. The Sierra Nevada Mountains extend along the eastern side of the State for about 450 miles, with nearly 100 peaks exceeding 10,000 feet (3,000 m) in height, the highest being Mount Whitney at 14,505 feet (4,421 m), the highest summit of the United States, excluding Alaska.

The eastern side is abrupt and rises from the plateau of Nevada, but the western slope, receiving nearly all the rainfall and delivering the rivers, has been worn into a series of tremendous canyons bordered by rocky minarets and towers. These canyons, often from 2,000 to 5,000 feet (600–1,500 m) in depth, become a marked feature of the range as one proceeds northward; over great portions of it they average probably not more than 20 miles apart.

The central part of this great mountain mass is known as the High Sierras, where Mount Whitney is surrounded by a large group of peaks not less than 13,000 feet (4,000 m) high, and the surrounding country for 300 square miles has an elevation of 8,000 feet (2,400 m). The explorer may wander for months in this wide wonderland among the clouds, traveling all the time and never seeing the same thing twice. Much of the ruggedness and beauty of the mountains is due to the erosive action of the vast glaciers that once existed on the higher summits, and which have left behind valleys and amphitheatres with towering walls, polished rock-expanses, glacial lakes and meadows and tumbling waterfalls.

Most beautiful of all is the unique scenery of the Yosemite Valley, where there are scores of magnificent waterfalls and sheer cliffs. The first sight of Yosemite, a mighty chasm in the heart of the mountains, is a vision to inspire awe. Emerging from the deep shadows of the pine forest, the view bursts upon you in a magnificence which compels silence. Mighty cliffs guard the entrance, and beyond these the rock-walled valley gleams in light. It was transformed into a U-shaped gorge during the Ice Age, when two mighty glaciers, uniting at the head of Yosemite Valley widened as well as deepened it.

Yosemite National Park

Yosemite National Park

All of the Sierra lakes are of glacial origin and there are some thousands of them. The finest of all is Lake Tahoe, 6,225 ft (1,897 m) above the sea, lying between the true Sierras and the Basin Ranges, with peaks on several sides rising 4,000–5,000 feet (1,200–1,500 m) above it. It is 1,500 feet (450 m) deep and its waters are of extraordinary purity. Clear Lake, in the Coast Range, is another beautiful sheet of water. Lake Mono, on the other hand, is so saturated with various mineral substances such as salt, lime, borax, and carbonate of soda, that it is intensely bitter and saline, and the human body floats in it very lightly.

In the north lies the great gold region discovered in 1848. In the days of the gold rush, the region was the center of the most intense activity. Along the gulches and river-banks throngs of miners toiled with rocker and pan, looking for nuggets and dust of yellow gold. Now their communities are mere ruins or "ghost towns," and many have disappeared. These hills of the lower Sierra are themselves rugged half-mountains with a succession of lovely mountain meadows. At the north end the Sierra Nevada is the active volcano of Lassen Peak, rising from the surrounding hills to an altitude of 10,457 ft (3,187 m). This is the southernmost volcano in the Cascade Volcanic Arc which heads north into Oregon.

Desert Region

South and east of the mountains California becomes the hot and arid region of the Mohave and Colorado deserts. Here there is practically no rainfall, and the thermometer rises to 130°F in the shade.

Mohave desert

The northern half, the Mohave desert, is a mountainous barren tract of land, about 2,000 feet (600 m) above sea-level. It is an exceedingly dry region, cut up by numerous irregular ridges of bare, rocky mountains, with intervening valleys of sand and rocks. Here are mesquite tree, with their pale green leaves, the yuccas that grow sometimes 15 feet (5 m) high, the ocotillo, with its array of whiplike branches, and many the cacti that grow upon the plains. The mountain ranges present strange and weird outlines against the sky, especially in the swift lurid light-effects of sunset and dawn. In the center rise abruptly the Calico Hills, remarkable because of their strange coloration, red, yellow, violet, bright green, pink, crimson, and brown, each hill has its own distinctive hue.

The region which lies east of the Sierra Nevada is broken by ranges and groups of arid, volcanic hills, and deep salt-covered valleys. Owen's River runs through it from north to south for some 180 miles. Near Owen's lake the scenery is extremely grand: the valley here is very narrow, and on either side the mountains rise from 7,000 to 10,000 feet (2,100–3,000 m) above the lake and river. Still further to the east some 40 miles from the lake is the infamous Death Valley, some 50 miles long and 5 to 10 miles broad. It received its name when an emigrant wagon-train suffered catastrophe here in 1849, and many lives were snuffed out in the intense heat. It is below sea level (about 282 feet / 86 m), and altogether is one of the most remarkable physical features of California. The mountains about it are high and bare and brilliant with varied colours.

Colorado desert

The southern part, the Colorado desert, is an open basin region with sandy soil and scanty vegetation. On the east is the Colorado River which flows along the border with Arizona. The plants consists of the drought-resisting species native to the Southwest. The agave, ocotillo, cactus, yucca, the creosote bush, and the mesquite tree grow upon these plains and slopes, and after every refreshing shower there spring up short-lived flowering shrubs that carpet the desert with a mass of varied color.

A number of creeks or so-called rivers, with beds that are normally dry, flow centrally toward the saline lake known as Salton Sea. This is the lowest part of basin, the surface of the lake being 236 feet (72 meters) below sea level.

To the west is Palm Springs, one of California's renowned resorts. It sits at the eastern base of the San Jacinto mountains, which tower to 11,000 feet (3,350 m) above. Here reposes an oasis of greenery in the shade of palms and vines and fruit trees. Sheltered secret canyons, with palm trees beside running streams, lie under the two-mile-high bulk of Mount San Jacinto.

_anza-borrego_state_park,_san_diego_co,_ca_-4b_(32196594822).jpg) Anza-Borrego Desert State Park

Anza-Borrego Desert State Park

What is the nature of California like?

California embraces areas of every life-zone of North America, from the realm of dwarf mountain pine to giant cactus. California has some of the most magnificent forests of the world. The variety of forest trees is not great, but some of the California trees are unique, and the coniferous forests which make up most of California's woodland surpass all similar forests in the size and beauty of the trees. These trees include pitch pines, cypresses and yews, and its two species of redwood or sequoia.

Plants

The coast redwood (Sequoia sempervirens) grows only in a narrow strip on the Coast Range from Southern Oregon down to Monterey in a habitat of heavy rain and fog. These trees attain very often a height of more than 300 feet (90 m), frequently of 350 feet (105 m) and more. In maturity the huge trunk rises to a great height with a crown which is a pointed spire like fir or spruce. The bark is red, deeply furrowed, with the ridges often much curved and twisted. The twigs are densely clothed with flat spreading foliage. The wood contains no pitch and much water, and in a green condition will not burn thus making it immune to forest fires.

The giant sequoia (Sequoiadendron giganteum) is native wholly to the Sierra Nevada. This tree grows typically in scattered groves with other tree species. It is a tree of the mountains, growing mostly above 5,000 feet (1,500 m) and below 8,400 feet (2,500 m) in a 250 mile strip of the Sierra. Although shorter than the coast redwood, they are greatest in bulk possessing a wider trunk. Various individuals stand over 300 feet (90 m) tall, and a diameter of 25 feet (8 m) is not rare. The leaves of the giant sequoia are awl-like in massy pendant plumes. Their crowns become rounded in maturity and are often are fashioned like inverted bowls.

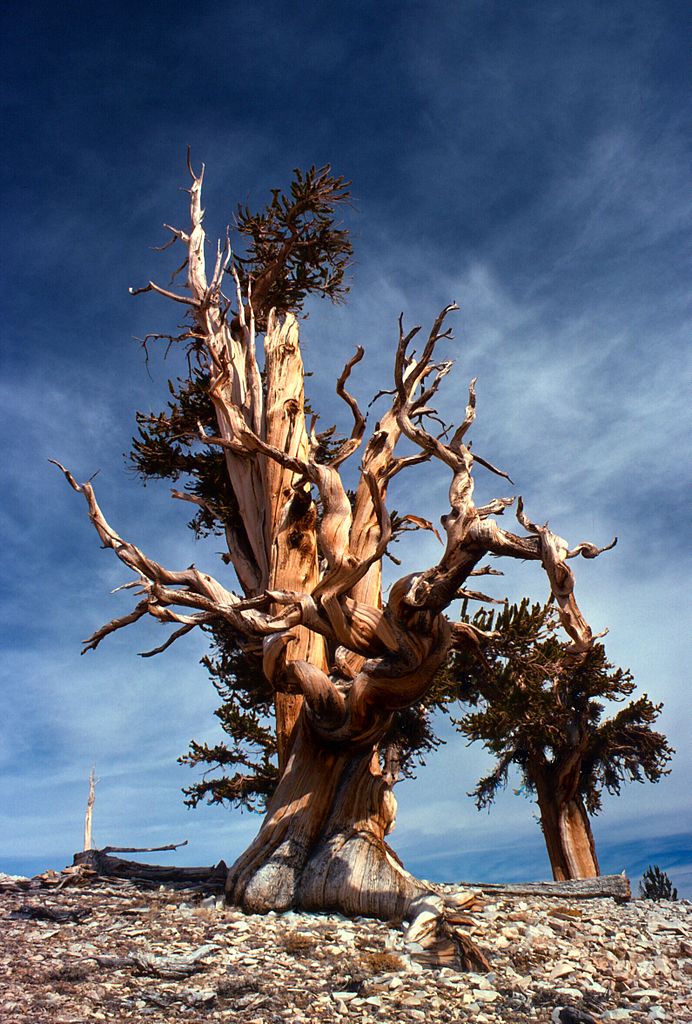

Among pine trees, the tallest is the sugar pine which usually grows at great altitudes in the mountains, both in the Sierra and in the Coast Range. It can attain 200 feet (60 m) or more when full grown; its name derives from a sweet resinous gum it exudes. Other tall trees of the Sierra mountains include the ponderosa pine, western white pine, and the Douglas fir, all attaining 200 feet (60 m). The white fir (Abies concolor) and the red fir (Abies magnifica), standing 200 to 250 feet (60–75 m) tall, make up much of the forest at higher altitudes from 5,000 to 9,000 feet (1,500–2,700 m). Above this come the lodgepole pines (Pinus contorta) and the bristlecone pines (Pinus longaeva), the latter known for being among the oldest trees on Earth. The highest-elevation pine trees at 10,000 to 12,000 feet (3,000–3,650 m) are the whitebark pine (Pinus albicaulis) and limber pine (Pinus flexilis) which grow in a tangle, and usually mark the tree line.

Many trees of California are confined to "tree islands" where they are native nowhere else in the world. This includes the Monterey pines and Monterey cypresses of the central coastland; and the tall Santa Lucia firs confined to steep-sided slopes and the bottoms of rocky canyons in the Santa Lucia Mountains. One of the most strikingly beautiful of California trees is the Pacific madrone (Arbutus menziesii)—an evergreen which sometimes attains a height of fifty feet (15 m), growing often in association with the redwoods. It has a bark deep red and smooth, but this peels off at regular seasons, revealing satiny new bark of pea-green color. The leaves are oval, lustrous, vivid green, contrasting with its bark and fleshy red berries in clusters.Oaks are abundant in California; they are especially characteristic of the Central Valley, where they grow in magnificent groves. Largest and most typical oak of California is the valley oak (Quercus lobata) native in the central valleys, with spreading, drooping branches. The California black oak (Quercus kelloggii) is a majestic and beautiful tree found in the mountain forests as well as in groves in the upland flats and valleys; the canyon live oak (Quercus chrysolepis) dominates extensive woods in the Sierra Nevada; and the California live oak (Quercus agrifolia) is a beautiful evergreen that thrives in the coastal environment. Across the Coast Range and the lower western slopes of the Sierra Nevada, much of the vegetation is chaparral—that is, dwarf oaks in association with thorny bushes forming almost impenetrable thickets. The name comes from the Spanish word chaparro signifying a scrub live-oak, small and evergreen.

The deserts of California have a flora utterly distinct from the rest of the State. Here the indigenous plants are the creosote bush, mesquite tree, desert acacia, yucca (especially the Spanish-bayonet and Joshua tree), and cactus. These grow often in profusion upon the plains and slopes, and offer such a contrast to the rest of California that it almost seems like plant life from another planet.

Wildflowers run riot in California, each month marked by a special growth. In the spring, when most of the wildflowers bloom they cover not only the plains and foothill slopes, but often show their colors upon the tops of mountains. Forests abound with them, and even the deserts and arid plains are graced by their presence. Poppies, cream-cups, goldfields, cluster-lilies, tidy tips, fairy lanterns, larkspurs, violets and hundreds of other varieties of native flowers. Likewise there are lupines, blue and white and yellow; the Indian paintbrush; sticky monkey-flowers; mariposa lilies; goldenrods; baby blue eyes; leopard lilies;—all jostling one another in the meadows. California's official State flower is the California poppy (Eschscholzia californica), which can cover vast areas of meadow with golden flowers.

California poppies near Lake Elsinore

California poppies near Lake Elsinore

Animals

The black bear still roams the highlands of northwestern California and the Sierra Nevada, but the famous California grizzly bear, a subspecies of the grizzly bear, is sadly extinct. Cougars can be found in forested areas and the mountains, and coyotes roam on or near the plains. Several kinds of foxes are native to California, and the bobcat roams widely.

Formerly abundant, the elk or wapiti remains now only in small protected bands in the forests of the western counties. More widespread is the graceful black-tailed deer, and the mule deer—notable for its long mule-like ears. The pronghorn, an antelope-like creature, once roamed in vast herds throughout the dry plains and valleys of California, but today is found only in the northeastern part of the state.

There are various species of ground-squirrels and gophers, which are very abundant. The Douglas red squirrel is ubiquitous in the Sierran forests and their most conspicuous inhabitant. Chipmunks swarm in the northern mountain ranges. The yellow-bellied marmot, a large ground squirrel, is found in the higher mountains. California has a full quota of raccoons, badgers, porcupines, gophers, field mice, and other smaller mammals.

The elephant seal breeds on offshore islands and remoter beaches. Sea lions resort in large numbers to the near-shore rocks and islands. The endangered northern fur seal breeds in the Channel Islands. Sea otters, which were reduced to single colony of about fifty individuals in 1938, can now be found up and down the Central Coast.

Noteworthy in the Desert Region are a variety of snakes and lizards, desert rats and mice; and, among birds, the cactus wren, thrasher, desert sparrow, common nighthawk, mockingbird, and Greater roadrunner (Geococcyx californianus).

The California condor, the largest flying bird in North America, became extinct in the wild in 1987, but has since been reintroduced to the coastal mountains of central and southern California. The bald eagle (the one which stands as the emblem of the United States) has breeding poulations in the eastern and southern mountains. Golden eagles occupy the mountains and coastal areas of California. Ospreys are found beside clear waters both fresh and salt.

The bluebird is represented by two species, the Western bluebird and Mountain bluebird; it is a great favorite, on account of both its beauty and its song. Then there is the Western meadowlark, almost as large as a dove, but with a striking yellow breast. The American dipper, entirely slate-colored, lives on the margin of torrents, feeding on water insects, which it captures by diving, swimming, or walking under water. The wrentit, the only species in its genus, lives in the chaparral belt. The California scrub jay, a blue headed bird, inhabits oak-groves and other woods in the valleys. The yellow-billed magpie, another purely Californian bird, is common in the valleys. Blackbirds, linnets, finches, towhees, sparrows, and grosbeaks, all abound in California. Swifts and swallows are myriad. The Western tanager spends the summer in California and northward, and is brilliant in both plumage and song.

Hummingbirds are more partial to California than to any region United States, and three or four are year-round residents. Anna's hummingbird is green, with its throat a brilliant violet-purple. The rufous hummingbird is rust-colored, its throat orange-red, and haunts California's gardens. Allen's hummingbird, similar to the rufous hummingbird, but with a green back. The black-chinned hummingbird, small with a black, shimmering throat.

Of the water birds, the swimmers, many representatives are present: geese, ducks, cormorants, gulls, terns, loons, and pelicans. The sandhill crane, and several kinds of herons, are among the waders found along California shores; and the American coot, a slaty-blue duck-like bird, is here as elsewhere.

What is the climate of California like?

The climate of California is milder and more uniform than almost any other part of the United States. Two seasons, the wet and the dry, divide the year; but as one goes north the winter rain is found to begin earlier and last longer; while, on the other hand the south-eastern corner of the State is almost rainless. Winters are mild everywhere except in the high mountains, and the heat of summer is greatly lessened by the dryness of the air. The climate of the coast is wonderfully uniform. An on-shore breeze blows every summer day; in the evening it is replaced by a night-fog, and cooler air comes down from the mountain sides. The only drawback to the Californian summer is the dust which takes a while to become accustomed to. The central valleys experience greater extremes of temperature with hotter days and colder nights, but even on the high peaks of the Sierra, the summer days are delightfully mild and clear and without rain.

The southeastern deserts of California are exceedingly dry with very high temperatures. In summer the thermometer ranges above 90°F (30°C), sometimes for weeks, both by night and by day, while the maximum may for days in succession be as high as 120°F (50°C). Yet the surrounding country is not devoid of vegetation; the hills are very fertile when it rains, and the herbs and shrubs spring to life.

California has a rainy and a dry season. The rains begin in the north early in autumn, but do not fall in central or southern California in any great quantity until December—often the month of greatest rain. The rainy season ends in May, and the summer months are very dry. The rainfall increases gradually from south to north, but many places in northern, central, and southern California have more than 200 perfectly clear days in a year. The northwest counties are very wet and many localities here have annual rainfalls of 60 inches (1,500 mm). On the south coast around San Diego annual rainfall is only about 10 inches (250 mm), and in the southern deserts 2 inches (50 mm) is normal.

Snow is very rare on the coast and in the valleys, and never remains for many days except in the north. The High Sierra mountains experience mostly snowfall, and this snow as it melts during the summer provides water of immense importance to the State. The total amount of rain which falls from year to year is very variable, and this can cause a succession of dry years leading to severe droughts.

| Climate data for Sacramento, California (1991–2020) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °F (°C) | 56.0 (13.3) | 61.3 (16.3) | 66.3 (19.1) | 72.1 (22.3) | 80.3 (26.8) | 87.9 (31.1) | 92.6 (33.7) | 91.9 (33.3) | 88.5 (31.4) | 78.8 (26.0) | 65.0 (18.3) | 56.0 (13.3) | 74.7 (23.7) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 47.6 (8.7) | 51.4 (10.8) | 55.4 (13.0) | 59.5 (15.3) | 66.1 (18.9) | 72.2 (22.3) | 75.9 (24.4) | 75.3 (24.1) | 72.5 (22.5) | 64.5 (18.1) | 53.9 (12.2) | 47.3 (8.5) | 61.8 (16.6) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 39.2 (4.0) | 41.5 (5.3) | 44.5 (6.9) | 47.0 (8.3) | 52.0 (11.1) | 56.5 (13.6) | 59.2 (15.1) | 58.8 (14.9) | 56.5 (13.6) | 50.3 (10.2) | 42.7 (5.9) | 38.5 (3.6) | 48.9 (9.4) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 3.66 (93) | 3.49 (89) | 2.68 (68) | 1.26 (32) | 0.75 (19) | 0.23 (5.8) | trace | 0.04 (1.0) | 0.09 (2.3) | 0.85 (22) | 1.66 (42) | 3.43 (87) | 18.14 (461) |

| Source: NOAA | |||||||||||||

View of mountains, Mammoth Lakes

View of mountains, Mammoth Lakes

The official websites

California

The Golden State

| Location: | On the Pacific coast of the southwestern United States |

| Coordinates: | 37° 00′ N, 120° 00′ W |

| Size: | • 1,260 km N-S; 560 km E-W • 780 miles N-S; 350 miles E-W |

| Terrain: | Extensive seacoast, High mountains, the Sierra Nevada, in the east. Coast Ranges in the west. Central Valley in the middle. Mojave and Colorado deserts in the southeast. |

| Climate: | Two seasons—a long, dry summer, with low humidity and cool evenings, and a mild, rainy winter—except in the high mountains, where four seasons prevail and snow lasts from November to April. |

| Highest point: | Mount Whitney 4,421 m / 14,505 ft |

| Forest: | 33% (2016) (source) |

| Population: | 39,368,078 (2020) |

| Population density: | Low-to-Medium (98/km²) |

| Capital: | Sacramento |

| Languages: | English; Spanish; Other (includes Chinese, Tagalog, Vietnamese, Korean) |

| Human Development Index: | Very High (0.936) |